Doula Is a Verb

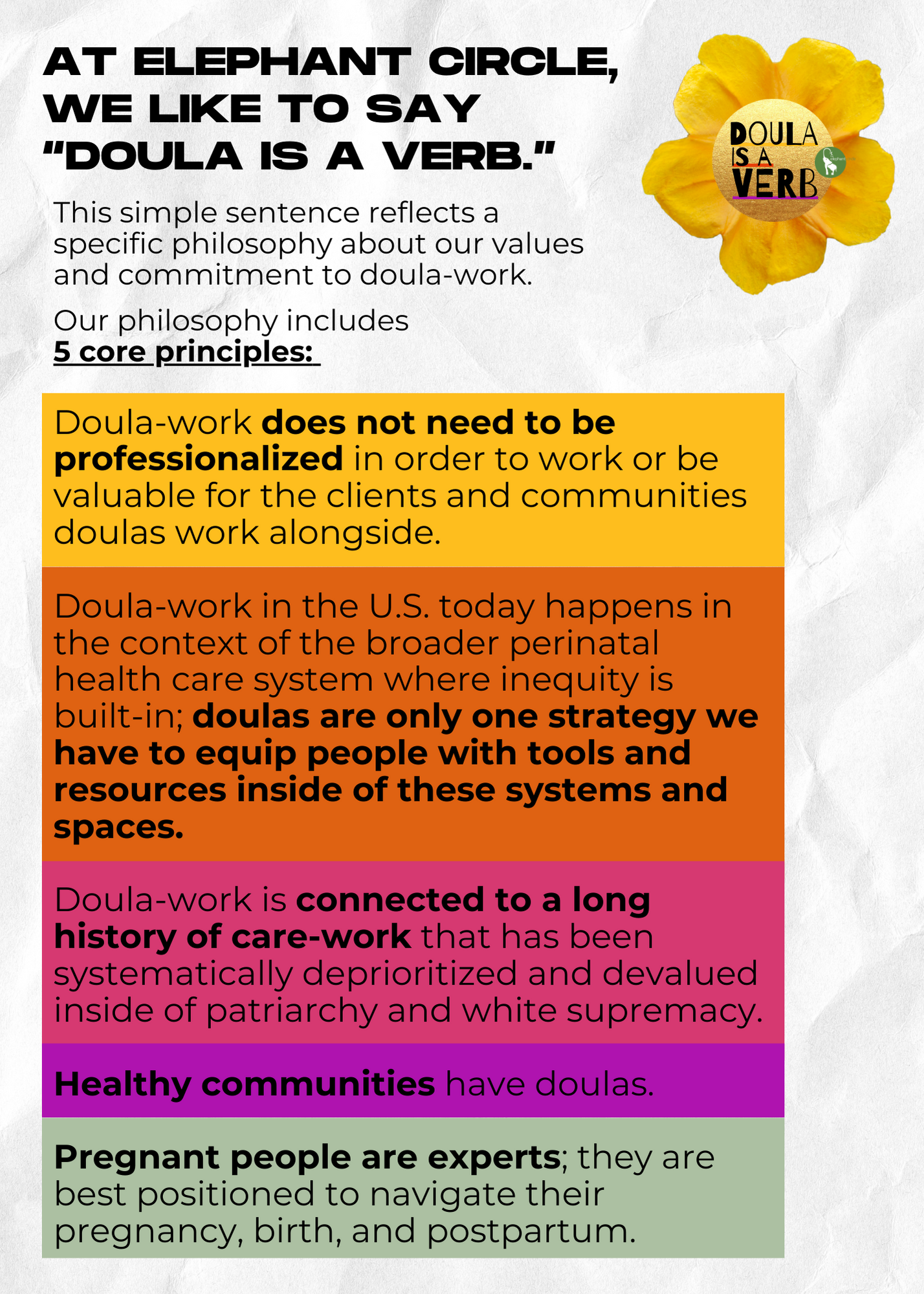

At Elephant Circle, we like to say “Doula Is a Verb.”

This simple sentence reflects a specific philosophy about our values and commitment to doula-work*.

Our philosophy includes 5 core principles:

Doula-work does not need to be professionalized in order to work or be valuable for the clients and communities doulas work alongside.

Doula-work in the U.S. today happens in the context of the broader perinatal health care system where inequity is built-in; doulas are only one strategy we have to equip people with tools and resources inside of these systems and spaces.

Doula-work is connected to a long history of care-work that has been systematically deprioritized and devalued inside of patriarchy and white supremacy.

Healthy communities have doulas.

Pregnant people are experts; they are best positioned to navigate their pregnancy, birth, and postpartum.

*Learn more about this term here: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/57126eff60b5e92c3a226a53/t/638f562c3ebfa36a53bf88de/1670338102604/FINAL+Advocating+for+Birthworkers+in+Colorado.pdf

1: Doula-work does not need to be professionalized in order to be effective

What do we mean by “professionalized”? Professionalization is a process that turns an activity into a distinct, standardized occupation (a “profession”). This process is often inspired by a desire to make more money from the activity. To make more money from the activity, people need to see it as an activity with a value that you can put a price tag on. To put a price on it, you have to be able to show exactly what it is, and distinguish it from what it is not. This usually requires distinguishing it from activities that aren’t in the market, like hobbies, religious callings, family duties, and relationship practices. You also have to put it into the market. Market rules can include fees, proof of credentials for the activity, and demonstration of standards.

People in your world probably have experiences with this. Maybe you have a family member who cuts hair but who couldn’t open a salon because they aren’t a licensed cosmetologist; or a friend who makes amazing food but runs into all kinds of roadblocks when they want to open a food truck. This process is not unique to doulas. As you think about it you can see how it is a process that involves a change in how people think about the activity, as well as a change in the economics of the activity, and the regulation of the activity. It deeply impacts who can do the activity and what the activity can be.

A stark example of professionalization in health care is midwifery. This process is still underway in the U.S. (and globally), and is well documented for those who want to learn more. Briefly, Midwifery is a human practice of support for pregnancy that has been happening across time and cultures. In the U.S. the effort to professionalize medicine, specifically obstetrics, included an effort to distinguish between the activities of obstetricians and the activities of midwives (even though many of the activities were the same). This process led to the criminalization and sidelining of midwifery, which reduced access to midwives, which then led to the professionalization of midwifery as a way to bring them back into the market and increase access. It’s a huge topic by itself, but if you’re talking or thinking about doula professionalization you should definitely study midwifery.

There are many lessons that can be learned from the history of midwifery professionalization and it’s clear that professionalization comes with pros and cons. Reasonable minds can come to different conclusions about those. But for us, one critical fact stands out: doula work does not need to be professionalized in order to work. The great outcomes policymakers tout, the intervention against inequities that doulas offer, and simply, the many benefits that flow from having a doula, exist because of the activities of doula-work. The benefits do not rely on (and may even be reduced by) doulas being a profession. In fact, the concept of “professionalism” has historically been weaponized against doulas, especially doulas of color – creating expectations that birthworkers adhere to standards of white supremacy culture masquerading as “professionalism”, and marginalizing those that do not assimilate. For people who care about getting more of these benefits to more people it is essential that you keep this fact in mind: doula-work is effective because “doula” is a verb.

2: Doula-work in the U.S. today happens in the context of the broader perinatal health care system where inequity is built-in

It turns out that the activities of doula-work, the action in the action-word, have been shown to improve outcomes. In studies, this activity has been defined as “one-to-one intrapartum support.” That having personal, individual, support helps people should be no surprise. The data bears out what we know logically and intuitively. Helping, helps! What may be less obvious is that one-to-one support is lacking in perinatal health care because it wasn’t built-in.

Why wasn’t it built-in and how do we know this? It wasn’t built in because the pregnant woman wasn’t the priority. The social and scientific significance of the pregnancy was more important and this significance varied by race and class. So, for example, certain obstetric procedures were developed on the bodies of enslaved Black women because those procedures could both support their value as property and increase the value of the obstetricians who could perform the procedures. But the support these women may need was not a consideration in the slightest. Even for privileged white women, the social and scientific significance of pregnancy was more important than their personal needs: the fact that they had a uterus dictated their purpose (pregnancy) and their position (secondary) and any support they may get was delivered through this lens.

Of course there are many perinatal health care providers today that see their pregnant clients as worthy of individual support. But they will have learned their trade from people who learned their trade from people who did not. They will practice in settings that were designed and built and bankrolled by people who did not see pregnant clients as worthy of individual support. This history is only 3 or 4 generations old. It is as present as your great-grandma’s recipes.

Doing the work of supporting a pregnant person one-on-one may help that person feel helped, and that may improve their lot. But doing the work of supporting a pregnant person one-on-one, even lots of them over and over, cannot change the shape of the system by itself. If support is an action that works, and we want more of it in the system, we’ve got to build it in. Doulas should not be the only people doing that action. Doula is a verb that everyone in the system could do - if it were built that way.

It is worth noting that midwifery incorporates the value of the pregnant person more effectively than other models (as illustrated by various surveys and data) and part of the inequity built-in to the status-quo comes from the marginalization of midwives. Incorporating doulas into the system cannot resolve this inequity. A system that truly addresses perinatal inequities includes midwives.

3. Doula-work is connected to a long history of care-work that has been systematically deprioritized and devalued

Work is part of the human condition. Every culture across time has had a system for organizing work. One of the ways work has been organized is by separating the “domestic” work from “real” work.

Work that drives markets has been prioritized in the U.S. and has relied on “domestic work” being available and undervalued. Work involving the care of children, elders, people with disabilities, pregnant and postpartum people, and homes, has been considered “domestic work” and associated with women and lower-classes. Today, the majority of “domestic work” as a profession, is done by women of color (over 90% of domestic workers are women and Black, Hispanic and Asian American/Pacific Islander women are vastly overrepresented as a proportion), and “unpaid family work” like care of dependents and households is still performed mostly by women.

At Elephant Circle we are aware that work is not neutral, that work is about power. So the issue of doula-work has to be considered in the context of the organization of work in society more broadly. We see doula-work, that action-verb of one-on-one care and support, as part of the broad umbrella of care-work. Ai-jen-Poo, Director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, calls care-work, “the work that makes all other work possible.” We need to think about what work doula-work makes possible.

Care-work has been marginalized socially, culturally and through explicit policies. For example, when other workers got protections through the Fair Labor Standards Act one hundred years ago, those who performed care-work were explicitly left out. This had the effect of maintaining racialized and gendered inequality. The inequality was the point.

Because inequality was built in, we need to think about what inequalities the organization of doula-work maintains, and how we can organize doula-work to dismantle inequities.

4. Healthy communities have doulas.

Along with the idea that doulas can address inequities in perinatal outcomes is the idea that doulas can bring culturally congruent care. In this vision, doulas reflect the communities they are in and are able to step in to care for the people in their community who need them, and that money isn’t a barrier to that care for the people who need it or the people giving. We love this vision!

But we keep in mind that the process of culturally congruent care is one that happens spontaneously in communities. Culturally congruent care isn’t “out there.” People care for each other as part of social-mammalian systems. Social-mammalian systems are ordered for in-group care. We already know how to do this! It’s just that things get in the way. We are concerned that by focusing on doulas as the solution we lose sight of where the problem actually lies. It isn’t that we lack the capacity or awareness to care, it is that culturally congruent care has been disrupted.

Some of the things that disrupt our social-mammalian instincts to care for each other are 1) the marginalization of care-work (see above), 2) socially constructed timelines and calendars that work against the rhythm of the perinatal period, 3) extractive economic policies, 4) organizing health systems around disease instead of wellness, and 5) oppression that defines some people as unworthy of care.

This is one reason why the image of the elephant circle is so important to us. It reminds us that we too are mammals. We already have a blueprint for this. We are part of the ecology. By looking to doulas as the solution we should be cautious not to take our eye off the problem. Setting up structures to support culturally competent doula care doesn’t guarantee that the structural problems are fixed. In fact, a surface solution could even distract from the problem in the short term. We want to see systems that are built for our mammalian circles, and protect against things that disrupt us.

5. The pregnant person is best positioned to navigate their pregnancy, birth, and postpartum.

Along those lines, one of the inequities built-in to the system, as we have discussed, is how the pregnant person is not the priority. To the extent that “doula” is the verb, the pregnant person is the noun, the subject of the sentence.

We don’t want to lose sight of the pregnant person. As the studies and our intuition show, doula-work can make a difference. But if the pregnant person’s life circumstances are dire, that support can only go so far. If the pregnant person is still not a priority in the system, that support can only go so far. Since doula-work is some of the only work in the current perinatal care system dedicated exclusively to the pregnant person, it is a powerful tool for reorienting the system. But it’s not the only tool and maybe not even the best one.

Doula-care can improve outcomes. But strong, healthy pregnant people who are respected, prioritized, and resourced, also improve outcomes. Keeping the focus on pregnant people themselves is key.

In conclusion, Doula is a Verb is how we practice doulaing, how we organize doulas, and a political-orientation to the role of doulas in caring for and supporting people across the perinatal period. It’s a practice of principles that reorient the perinatal system so that care is a top function and priority. Care isn’t just an intention you hold in your heart, it’s a way of taking action that anyone and everyone can do. This practice is also a way of resisting and reversing built-in inequities, so that women, people of color, and gender nonconforming birthing people are healthy and free.